Stan Druckenmiller recently elucidated: “Earnings don’t move the overall market; it’s the Federal Reserve Board… focus on the central banks and focus on the movement of liquidity… most people in the market are looking for earnings and conventional measures. It’s liquidity that moves markets.”

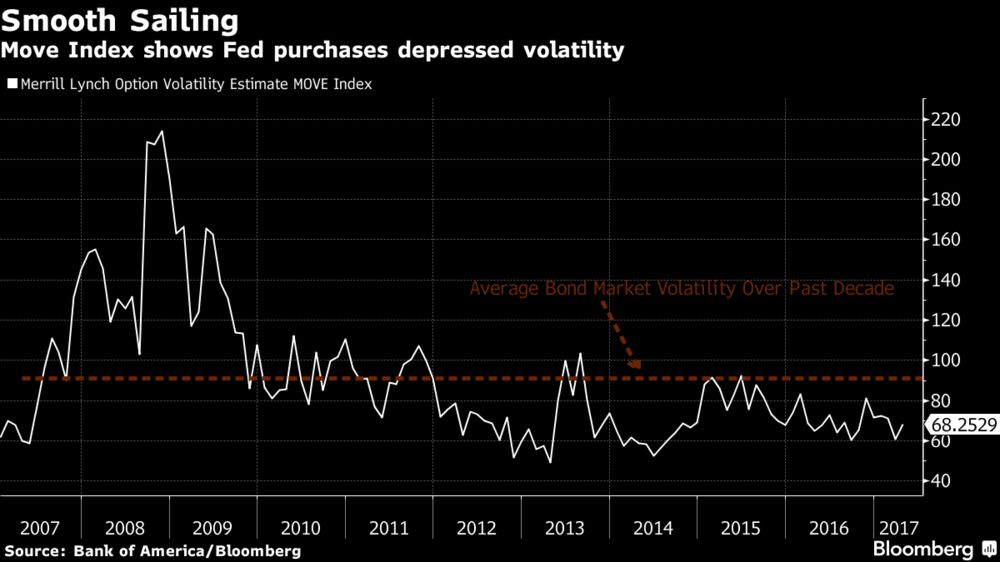

Even with the bond market’s muted response to the Federal Reserve’s plan to begin winding down its almost $4.3 trillion portfolio of mortgage and Treasury securities, there are plenty of reasons why the calm probably won’t last.

Out of style for almost a decade, volatility may be on its way back if you take a closer look at the mechanics of the Treasury and mortgage markets. Despite the Fed’s mantra of seeking to carry out its policy shift in a “gradual and predictable manner,” analysts say the effects of ending the reinvestment of the proceeds from maturing securities will still be felt.

This is the “most highly anticipated event in central-bank history,” said Walter Schmidt, senior vice president of structured products at FTN Financial in Chicago. “We’ve known this for two years. We’ve been waiting for this.”

While the three rounds of Fed asset purchases that became known as quantitative easing sapped volatility, former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s comments in May 2013 that the central bank was considering scaling back purchases showed how quickly that can change. The so-called taper tantrum sent yields surging.

As the Fed begins to unwind, here are four reasons why we may see a renewal in volatility:

1. MBS Supply/Demand Shift

The Fed owns $1.77 trillion of agency mortgage-backed securities, about 31 percent of the market. As the central bank’s MBS holdings begin to roll off, mortgage spreads to Treasuries are going to have to widen to adjust for the additional supply, which some analysts estimate will begin at around $5 billion a month.

Since the Fed concluded quantitative easing in October 2014, the spread between Fannie Mae 30-year current coupon and Treasuries has been sitting between 90 and 114 basis points, below its historical average of about 137 basis points. Mortgage spreads may widen five to 10 basis points once the market prices in a certainty of tapering reinvestments and another 10 to 20 basis points over the longer term, Citigroup Inc. analysts estimate.

2. Increased Convexity Hedging

If the Fed decides to pause interest-rate hikes while letting the balance sheet shrink, mortgage rates are still going to rise because a large source of demand is disappearing. As a result, prepayment speeds, the pace at which borrowers pay off loans ahead of schedule, are going to fall, which will cause the duration of the securities to increase.

It’s still a double whammy if the Fed continues to raise rates. Fed tightening would push up the effective fed funds rates, also reducing prepayment speeds and increasing the average duration of the securities.

When rates rise, hedging against so-called convexity risk grows as the expected life of mortgage debt increases. That happens when refinancing slows and tends to leave holders more vulnerable to losses as lower-duration securities are more vulnerable to rising rates. By protecting against those potential losses (selling Treasuries or entering into swaps contracts), traders can end up making the bond market more turbulent.

3. Rise in Term Premium, Withdrawal from Risk Assets

As the market prepares for the Fed’s unwind, it should place upward pressure on the 10-year term premium, a measure of the extra compensation investors demand to hold a longer-term instruments instead of rolling over a series of short-dated obligations. The premium could rise 47 basis points over the course of 2018 and 2019 due to the reduction in duration, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch strategists. Higher term premiums, coupled with increased mortgage duration could also cause a steepening of the five- to 10-year yield curve.

There’s also a chance that an increase in term premium triggers a withdrawal from risk assets such as equities, which have risen to record highs during almost a decade of accommodative Fed policy, though “the risk asset link is not as certain,” according to Bank of America strategist Mark Cabana.

4. Surge in Front-End Treasury Rates

The front end of the Treasury market will have its own set of issues when the balance sheet starts to shrink. The Treasury Department will have to decide which portion of the curve it wants to issue more securities: The front-end, where Treasury bills outstanding comprise less than 13 percent of marketable debt, or the long-end to take advantage of 30-year bonds trading around 3 percent.

“Treasury is going to need to increase front-end supply pretty notably,” Cabana said. “Banks losing reserves will be looking to replicate those assets.”

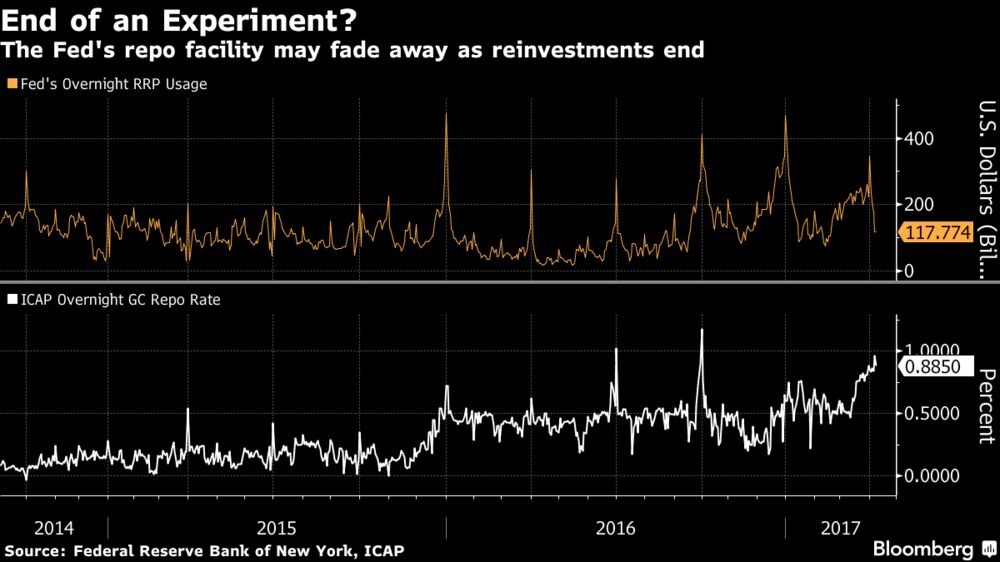

Assuming Treasury ramps up bill supply, rates on debt maturing in less than one year would likely rise, forcing up the overnight rate on Treasury repurchase agreements. That may cause usage at the Fed’s fixed-rate overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility to sink, as investors will pivot away from the operation.

“Overall, this should pressure rates higher, with banks having relatively more securities to finance in the repo market as time goes on,” said Scott Skyrm, managing director at Wedbush Securities in New York.

Courtesy of Bloomberg

Comments