As U.K.-based banks wait to see what life will be like after Brexit, one word -- passporting -- will speak volumes. If Prime Minister Theresa May can maintain the passporting rights of City of London banks, the U.K. stands to retain its status as a hub of global finance. If not, hope isn’t lost, but the alternative to passporting requires an arduous approval process and provides no secure basis for long-term planning.

1. What is passporting, anyway?

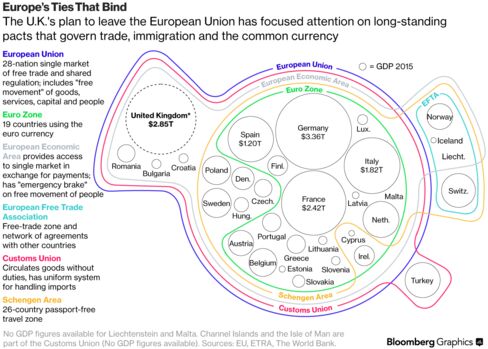

Passporting refers to the right of companies authorized in one country of the European Economic Area -- currently comprising the 28 EU states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway -- to sell their products and services throughout the bloc, accessing a $19 trillion integrated economy with more than 500 million citizens. There is not one financial passport, but rather a series of sector-specific agreements covering everything from banking to insurance and asset management. It’s why global firms such as Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley canhave the overwhelming bulk of their staff in London, with only satellite offices in other capitals like Paris and Frankfurt.

2. What banking activities are involved?

Passporting covers a range of activities, including deposit taking, derivatives trading, loan and bond underwriting, portfolio management, payment services, insurance and mortgage broking. A bank does not need a passport to conduct foreign exchange trading because that’s an unregulated activity.

3. What does passporting mean for U.K. banks?

London’s status as the world’s preeminent financial hub is due in no small part to the access companies based in the U.K. have to the EU’s single market. Eighty-seven percent of U.S. investment banks’ EU staff live in the U.K., which also boasts 78 percent of the region’s capital markets activity, according to New Financial, a research group. Consulting firm Oliver Wyman reckons around a fifth of the U.K.’s banking sector’s annual revenue -- between 23 billion pounds and 27 billion pounds -- is based on passporting access.

4. Is it just banks?

No. The EU is also an important market for U.K.-based insurance companies and asset managers. About 28 percent of insurance exports go to the bloc, according to Open Europe. The Investment Association estimates 21 percent of assets managed in the U.K. are connected to EU clients. Financial firms and associated businesses employ more than 2 million people nationwide and paid 66 billion pounds in tax last year, more than any other sector. The Financial Conduct Authority estimates about 5,500 U.K. firms use passporting to do business on the continent, and that 8,000 companies based in Europe use it to access the U.K. So the EU, too, has an incentive to strike a deal.

5. What would the loss of passporting mean?

Banks with their European headquarters in London say they would have to move thousands of employees to new subsidiary offices on the continent. "If we are outside the EU, and we do not have what would be a stable and long-term commitment that we would have access to the single market, we would have to do a lot of things that we do from London somewhere inside the EU27," said Rob Rooney, chief executive officer of Morgan Stanley International, the Wall Street firm’s most senior banker in Europe.

6. Who doesn’t benefit from passporting?

One example: A Hong Kong-based bank with no subsidiary office in the EU could not make use of the passporting system to do business within the European Union.

7. Will banks in the U.K. retain their passport?

It’s highly unlikely. Under current EU rules, the U.K. would have to become a member of the European Economic Area for British firms to retain unfettered access to the region’s single market. EEA membership comes at a price May might not be prepared to pay: contributing to the EU budget and following its rules, including the free movement of workers, while having no voice in making them.

8. What does the government say?

In July, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson said he expected the U.K. would keep its passporting rights. May says she will seek "to give British companies the maximum freedom to trade with and operate in the single market, and let European businesses do the same here," though not if that means giving up "control of immigration." Prior to becoming chancellor of the exchequer, Philip Hammond said, “I know and understand the importance of passporting.” He’s since retreated to pledging to aim for the “best” deal.

9. Is there a Plan B?

Maybe. If passporting is off the table, the U.K. may have to fall back on regulatory “equivalence,” which allows companies based outside the EU privileged, if targeted, market access. It would require the European Commission to recognize that the U.K.’s rules and oversight of specific business lines are as tough as -- equivalent to -- its own. The EU utilizes equivalence to reduce overlaps and capital costs for EU companies that must comply with rules in other countries. Most EU financial-services acts contain provisions for equivalence, including the updated markets rules known as MiFID II, which come into effect in 2018. Equivalence is also possible for some purposes in the EU’s bank capital rules and in Solvency II, which governs the insurance industry.

10. How might equivalence work in practice?

Take the recent agreement the commission struck with the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission on central counterparty clearing. EU law, in this case the European Market Infrastructure Regulation, allows companies based outside the bloc to provide clearing services in the EU on two main conditions. First, the commission has to determine that the country’s legal and supervisory systems are an “effective equivalent” to those in the EU; second, the companies must be recognized by the bloc’s markets regulator. The deal with the CFTC enabled companies such as Chicago-based CME Group Inc. to continue providing services to EU firms. Without it, traders would have faced higher EU capital requirements to clear swaps, futures and other derivatives in the U.S.

11. Why isn’t equivalence as good as passporting?

Passporting is a right, while equivalence is a privilege that can be unilaterally withdrawn by the European Commission at short notice. Also, equivalence doesn’t cover some core banking activities such as deposit taking and cross-border lending. Firms may have to endure a long period of uncertainty as the U.K. negotiates with the EU to have rules deemed equivalent. It took the EU four years to negotiate the CFTC deal.

12. Where does this leave the banks?

Facing an uncertain future with no clarity on what access they will have to the single market after Brexit, banks are lobbying May and EU leaders to strike an interim agreement which would allow them to continue to provide services across the EU from London beyond the end of the two-year negotiation period. In the meantime they are planning for the worst and accelerating plans to move thousands of employees and operations to the continent.

Courtesy of Bloomberg

Comments