Last week we posted a blip about Bardabunga; the largest volcano in Iceland experiencing an enormous increase in seismic activity of late and we recapped how the 2010 volcanic eruption in Iceland paralyzed air travel, shuttering a number of airports and stranding travelers across Europe (not to mention costing airlines billions in lost revenue).

To bring us up to date is Dem. site DailyKos which truly makes me love science even more. Sadly, I slept through much of it as a teen. What a fool was I.

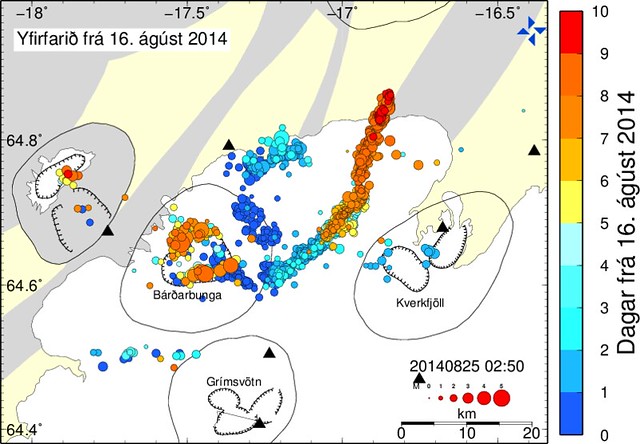

In any case, Bardabunga is far from calming down and indicators point to it's magma chamber not only expanding, but flowing right towards...........Askja; another volcano's magma chamber. Estimate now are that magma intrusion she's sent forth at an average rate of hundreds of cubic meters per second (similar to the flow rate of the Hudson River at New York City, straight through solid rock) has gone over 30 kilometers from Bárðarbunga's magma chamber, its end is no longer under the glacier Dyngjujökull, and it's now heading straight toward the magma chamber of Askja, another large, dangerous volcano in the highlands.

They've gone out of their way to give us some background on this area and trust me, it's brief and extremely interesting (seriously). You just know Nat Geo will be filming it all. One would certainly hope that this all dissipates or, if it blows, that everyone has moved to safety and there is no loss of life. I hate to say it though, just tell me if/when it blows beneath a glacier so I can short $DAL further. Enjoy-

Spring, 1875. Austfirðir (the Eastfjörds). Quakes had been felt late last year, but nothing had happened. There were no active volcanoes in the area, so there was nothing to be concerned about - or so was assumed. Had people walked a hundred miles into the highlands, they would have learned that a small eruption had started at the little known volcano Askja in January, but the area was sparsely populated.

However, on the 28th of March, all hell broke loose as Askja switched to a major Plinian eruption so powerful that her remoteness ceased to be sufficient. A fearsome plume rose above the Eastfjörds, all the way to the sea. Then came the pumice rain, while lightning crackled intensely. Hot chunks the size of tennis balls rained down across a vast area. A suffocating ash descended so thick that people could barely see their own hands. The eruption continued for a year at lower intensity.

The ash falls and pumice killed few people directly but led to the loss of large amounts of livestock. This, plus fear of further eruptions, caused widespread abandonment of towns in the Eastfjörds. A large chunk gave up on Iceland outright and moved to Manitoba and the northern US, forming towns such as Gimli, Manitoba. These people are now known in Iceland as the “vestur-íslendingar" (Western-Icelanders).

Today, Askja (whose name now means caldera, and is similar to the word for ash, "aska") is a popular tourist spot, where people come to see the massive caldera (easily visible from space) looking like a bullethole in Iceland, and to swim in the warm waters of a side section called Víti ("Hell"). But she's still highly dangerous, even when not erupting.

In 1907, two German scientists, Walter von Knebel and Max Rudloff, were investigating Askja in a boat... and neither they nor their boat was ever seen again, despite a major expedition launched by von Knebel's fiancee. Many theories over the ages surfaced, such as the prospect of a CO2 surge suffocating them, or even simple accidental drowning. However, just weeks before Bárðarbunga, the most likely cause made itself abundantly clear:

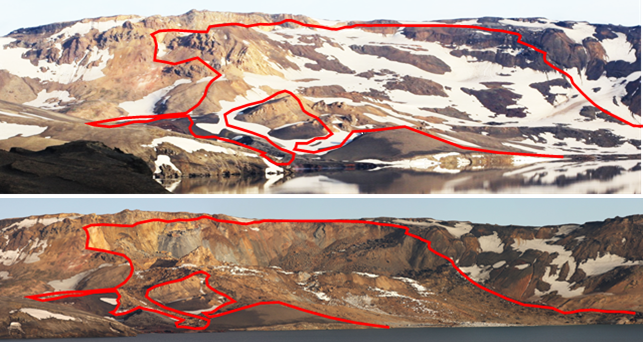

Around midnight, a large chunk of a side of the crater collapsed down into the caldera. Slamming into the water, it launched a 50 meter tidal wave ringing around the caldera, including into Víti. Had it not happened at midnight, the death toll would have been significant. This has now become the leading theory as to the cause of death of the scientists. The steep, unstable sides are triggered by the continual sinking of the core of the caldera

This raises a question:

Why the heck are we talking about Askja?

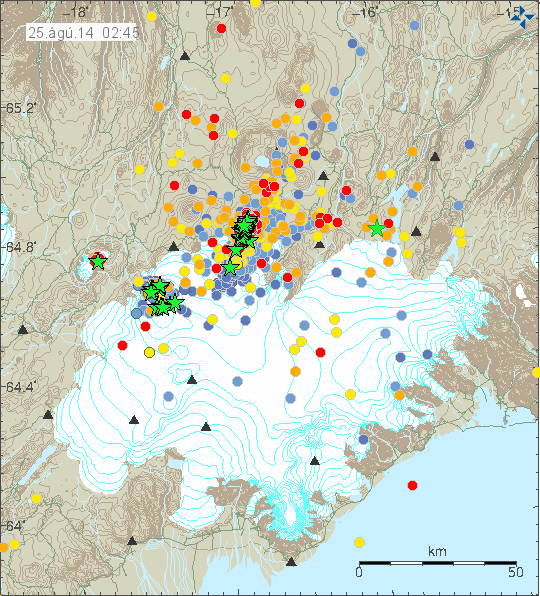

Because Bárðarbunga's magma intrusion is well on its way to linking the two magma chambers together:

Activity continues at a incredible rate, due to what is being described as a "ridiculous amount of magma" rapidly flows to the northeast and north:

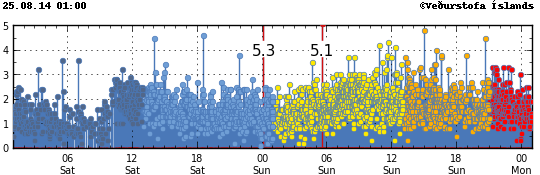

Two explanations have been put forth for why the already record level of activity rose so dramatically - one involves the magma breaking through colder rock, while the other involves a great increase in the magma flow. Regardless, surface tremors (often a key indicator of an eruption or imminent eruption) are up and regularly spiking at the meter nearest Bárðarbunga's caldera:

But you know where they're up even more? Askja:

So, where is all of this going? Páll Einarsson, a professor of Geophysics, presents a happy possibility. According to him, the presence of a long dike leading out from the caldera at 5-10 kilometers depth reminds him of the Kröflueldar ("Krafla Fires") (in Icelandic, lava fountain eruptions are often referred to as "fires"). Krafla erupted for nearly a decade, but at a slow rate, involving many subterranean magma intrusions. Consequently, the lava flows and gas emissions remained at levels that were not too dangerous - a "tourist eruption".

Haraldur Sigurðsson, another volcano expert, argues (using some of the same arguments as Páll) that it's wrong to think of these volcanoes that lie directly on the major rifts as distinct systems, that they usually stretch out over many dozens of kilometers or more. Examples include the connected eruptions of Katla and Eldgjá (Laki) in 970 (connected by a 55km dike) and the eruptions of Eldgjá (Laki) and Grímsvötn in 1783/4 (connected by a 70km dike). Askja, too, had a paired eruption with Sveinagjá in 1875. In all such cases, the lava that comes out of the systems is identical.

He raises the question, why don't we ever see quakes deeper than around 15km? The answer is simply, the rock there is too soft and breaks too easily for us to measure it. But there is no reason to believe that magma isn't flowing there either. Basically, that this shouldn't be viewed so much a magma intrusion / conduit, but a complete break in the crust (except at the surface). The surface expressions are just where the magma finds it easiest to break out, whether just through a single point, or through hundreds as in the case of a major rift eruption.

The exact nature of what will happen (since there's so many types and magnitudes of eruptions here) depends, according to him, on whether the rift cuts through Askja's magma chamber or goes around it. Regardless, he points out that the most likely point for magma to reach the surface is in the lowlands. Now that it has moved out from under the ice of Dyngjujökull, it's entered an area that should be easier to facilitate an eruption.

Lots of people have been commenting on the different types of eruptions we could expect, and honestly I'm not sure what to believe. However, I don't see in the historical record any evidence of anything that resembles the Krafla Fires in the Bárðarbunga area, so my intuition tells me that may be too optimistic. But one can hope. :) And even if it simply begins slow but changes form later, any letting off of pressure in a controlled manner would be a good thing.

As a final observation: we're starting to get even major earthquakes in side areas as well: under Tungnafellsjökull and right near Hágöngulón, the reservoir for the largest dam of its type in Europe, and there's lots of activity between there and the main magma conduit. While at this point there's considered no likelyhood of a jökulhlaup heading into the reservoir, they're not taking any risks; they'd already started draining down the reservoir. It's nice to see such precautionary measures taken even when a probability is low.

Update, 11:00 25 august: In an article on Visir.is, Sara Barsotti, a volcano expert for the Met Office, says she finds it unlikely that this event is going to end without an eruption - but whether that happens in the next hours, days, or even weeks or months is the question. She disagrees with Haraldur that it's likelier for the eruption to come up in the glacier-free area between Dyngujökull and Askja - she feels that that makes no difference.

In a different article, professor Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson states that a theory for the tremors and sudden rise in quake activity that led to the false alarm about a subglacial eruption is that the magma encountered a pocket of groundwater, which would (naturally) resemble the effects of hitting the glacier. He notes that this is just a theory and has not been proven.

Honestly, that sounds bad to me because the last thing I want in this magma is more dissolved gasses and pressure.

Minor update, 2:00: The magma intrusion is now said to be 35 kilometers long and contain 300 million cubic meters.

Comments